In his ground-breaking work, The Literary Mind (1996, Oxford University Press), the cognitive scientist Mark Turner, quotes the following lines from a Robert Browning Poem, Porphyria’s Lover.

The rain set early in tonight,

The sullen wind was soon awake,

It tore the elm-tops down for spite,

and did its worst to vex the lake.

Turner uses the imagery in the poem to show how we use metaphor to make sense of and share our thoughts about the world. This is nothing new. In poems, the wind can be angry, and the sun can be kind. However, Turner goes on to say that using one image or story to explain ourselves is not just for aesthetic pleasure but forms the very foundation of language. To illustrate he offers everyday examples of how language is story-based.

We animate non-living things to create a story.

- The stockmarket crashed.

- An idea grabbed hold of me and wouldn’t let go.

- AI is coming for our jobs.

We project images from one context to another in a story like way, the theme of birth for example.

- Necessity is the mother of invention.

- She’s a child of the modern age.

- Italian is the eldest daughter of Latin.

In making a case for the everyday mind as being fundamentally literary, Turner inadvertently offers a possible explanation as to why texts written for native speakers are so hard for language learners. They are rife with figurative language that can frustrate someone trying to find the meaning from a dictionary.

Here’s where graded readers can offer learners a more successful experience. Not all, but many graded readers take a strategic approach to supporting the beginning language learner. They do this by following certain parameters:

- Language is literal. The writing avoids idioms and figurative language.

- Sentences are modified to feature familiar grammatical patterns. For example, the writer may avoid embedded clauses, passive verb structures and certain phrasal verbs.

- Target vocabulary is reiterated so that readers can get multiple exposures to a word and its instances in a word family.

When I am working on a graded reader at the A2 level according to the Common European Framework (CEFR) (or second grade on the Fleish-Kinkaid scale), the goal is for readers to understand 95 to 98 percent of the words in the text. This means I must sacrifice beautiful words like crimson, and blush. Instead, I stick with red. I also resist the impulse to use expressions such as a raging storm or a run-down house because the allusion to anger or running might cause confusion if the reader is using a dictionary. Finally, I keep sentences short by avoiding noun and adjective clauses.

It often helps to read in another language because I am reminded that a story can only hold the reader’s attention if it is comprehensible. I am also reminded of the pleasure that comes from simply recognizing words and being able to follow the action.

I have also learned that dialog is a great vehicle for reiterating language in ways that can feel fresh. Different people at different points in the story can greet each other, make plans, or apologize using similar vocabulary patterns. The language of each of these functions gets repeated but always in new contexts.

This approach intentionally offers language learners what Paul Nation calls “an authentic reading experience.” It means that even beginning level language learners can read a story or text fluently without stopping to re-read or look up words. The experience allows for engagement with the ideas as opposed to battles with unknown words or metaphorical language. This is great for reading comprehension, and there is another benefit. When students can follow the text easily, it is also more likely that they can talk and write about it. In other words, graded readers not only create opportunities for receptive learning; they also set the stage for productive engagement with content.

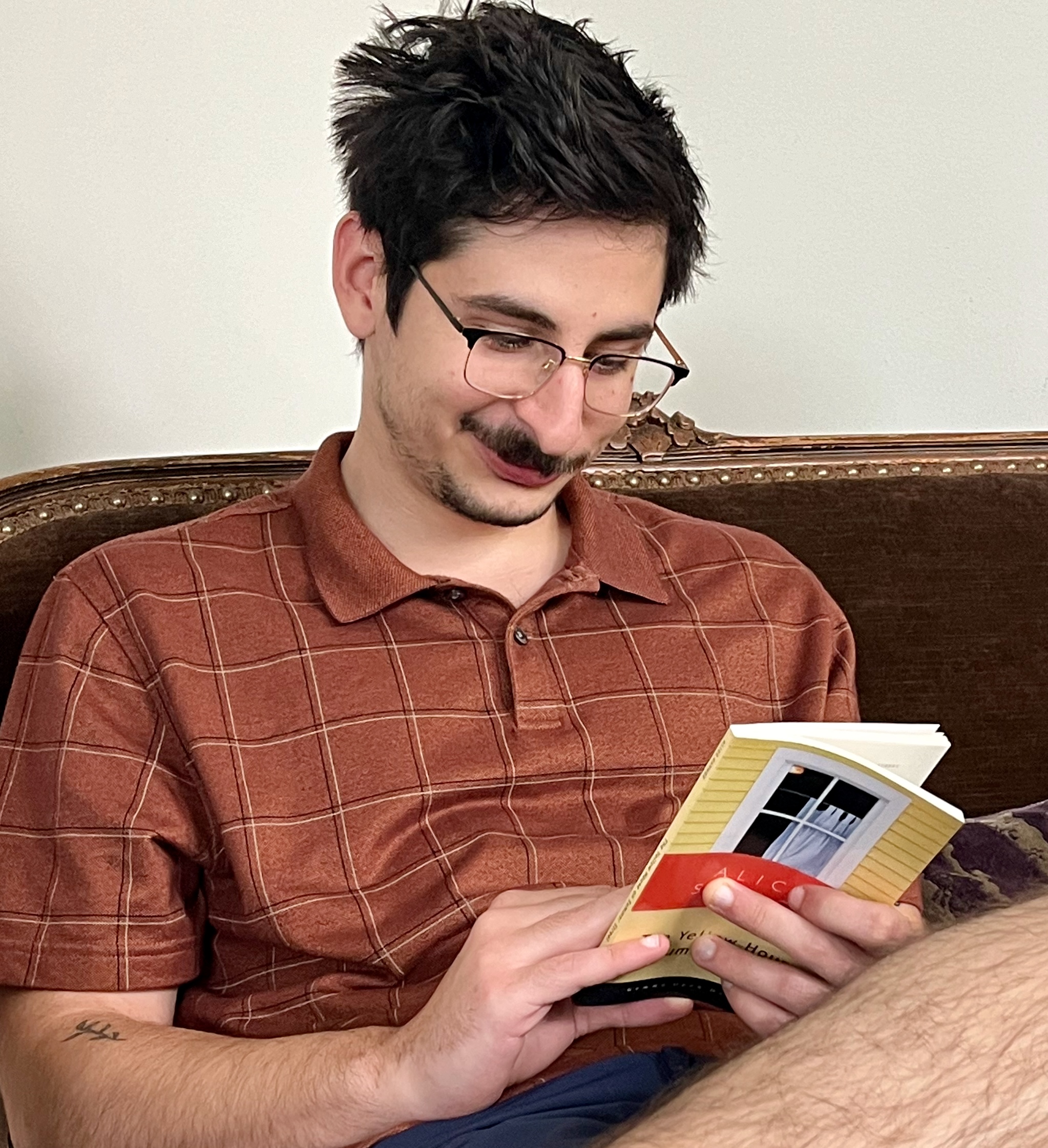

The following lesson plan ideas use The Yellow House Stories, published by GEMMA Media as source content, but the basic structure can be adapted for any graded reader.

LESSON PLANNING

Lessons can be very simple discussion questions designed to elicit connections between readers, their experiences and each other. They can foster understanding and critical thinking. To answer the questions for Mona below, students must articulate what Mona is doing and the character traits of Rashid and Joe. They must then apply that understanding in a new context.

- What happens in this chapter?

- Do you think Mona is doing the right thing?

- Are you more like Rashid or more like Joe?

Lessons can also be used for target grammar production. Here’s one for modals of advice. Students in groups can discuss and record their answers. In this example, Mona, is trying to convince her son’s boss to join her in encouraging Rashid to give up a dream of restaurant ownership. Mona thinks her son should go to medical school. Notice how the third open-ended question practices both grammar and critical thinking.

- What should/shouldn’t Shini do?

- What should/shouldn’t Mona do?

- Should parents choose their child’s career?

Lessons can also be used to target pronunciation. It is ideal to use scripts that are informed by the characters’ personalities and goals. In a dialog-rich book or a readers theater script, the character motivation can drive choices about sentence stress and intonation. The rehearsal process can act as a drill of sounds. Here’s an example from the free readers theater script that accompanies Mona. It can be found on the GEMMA Teacher Resources website.

Note the way Brita’s understanding of the situation changes as she realizes Joe is right about Mona and Vincent.

JOE Do you see that?

BRITA See what?

JOE Mona. She’s talking to Vincent.

BRITA And?

JOE I think there’s something going on between them.

BRITA You must be joking.

JOE No, look. See how they are standing.

BRITA You’re serious, aren’t you?

JOE Do you think I’m being ridiculous?

BRITA They’re just talking.

JOE She’s smiling. She hasn’t smiled since Rashid’s accident.

BRITA Oh, you’re right.

JOE See! I told you.

BRITA But don’t look. We should leave them alone.

JOE I’m right though, aren’t I?

BRITA Maybe . . . Shhh, here she comes. Don’t say anything.

Prosody is challenging in another language, but it is arguably the most important nonverbal aspect of communication. In fact, research suggests that people tend to find others more likeable or trustworthy when they understand the speaker’s feelings or intentions. When rehearsing a short scene like this, students are practicing prosody because each character’s feelings and emotions are evident in the text. Readers are also practicing linking, reductions, intonation, consonant clusters, stress emphasis, and vowel sounds.

Finally, learners can create their own scripts using the characters (or invent new ones). They can also improvise a roleplay among characters. One way to structure this is to assign a student to be a character with an important decision to make. Have that character come to the front. Students taking on the roles of other characters can come up and give advice.

Another useful lesson plan structure is to choose a conflict for an informal debate. It’s always helpful to start with some language for agreeing and disagreeing. For example, “You make a good point, but . . . “ Or “I understand, but I see things differently.” Or “Do you want to know what I think?” Next, divide the class in half. One half will take one side. The other half will take a different side. For example, in the Yellow House, the family chooses to invite a relative to come and live with them in their small home.

As – There can be problems when new immigrants try to live with relatives.

Bs – Sharing a home with new immigrants has many benefits.

Have the two groups gather to come up with ideas that support their side. Then have them form A/B pairs and try to convince the other side of their opinion. Have them change partners and repeat. Suggest they try out ways of politely disagreeing.

You can also have them do a fishbowl in which two students perform in front and get feedback on language and pronunciation.

In sum, Turner’s view of language as being fundamentally literary is fascinating in and of itself, but it also shows how difficult reading authentic materials can be. Graded readers are important for pleasure reading, but they can also provide accessible content that students can immediately put to use in productive classroom activities.

Categories: beginning multi-lingual writers, Conversation, EFL, ELT, ESL, ESOL, extensive reading, Fluency reading, Graded readers, grammar, pragmatics, reading, vocabulary